The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

-

Find CDs & Downloads

Amazon - UK - Germany - Canada - France - Japan

ArkivMusic - CD Universe

Find DVDs & Blu-ray

Amazon - UK - Germany - Canada - France - Japan

ArkivMusic-Video Universe

Find Scores & Sheet Music

Sheet Music Plus -

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

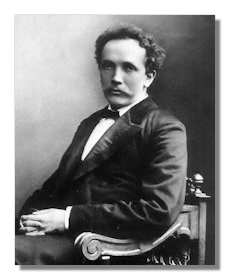

Richard Strauss

Annotated Discography

Recording companies have not exactly neglected Strauss. From the cylinder through the compact disc era, conductors have steadily preserved their interpretations of his instrumental works. In addition to the Big Four tone poems (Don Juan, Till Eulenspiegel, Tod und Verklärung, and – since Kubrick's 2001 – Also sprach Zarathustra), much of Strauss' less-known and even frankly minor work has gotten attention. Many of these recordings remain available, so you certainly needn't feel confined. On the other hand, compact discs tend not to linger in the bins. If you see something you want, pick it up. Several classic Strauss recordings are not currently available.

For those who want a comprehensive ramble through the Strauss orchestral catalogue, Kempe's landmark 3-volume, 9-CD survey on EMI certainly provides convenience. You may find better performances of individual works, but the set on the whole deserves the praise critics have given it.

Your choice should depend on how you view Strauss as an artist – not easily-resolved, for Strauss is one of the most elusive musical personalities. For me, the widely-held opinion of him as a sensationalist interested only in depicting a realistic surface simply won't do, although it does lead those who hold that opinion to certain performances, ones that execute the surface superbly and emphasize a rich orchestral tone. Certainly Strauss has this side. After all, he came to artistic maturity as the Naturalist movement, with its emphasis on detail, began. The big sound and striving for effect in the Wagner orchestra also undoubtedly influenced him. In some ways, Strauss reminds you of Dickens's Fat Boy, who "wants to make your flesh creep." At the least, Strauss wants to astonish you, and he does, brilliantly, with orchestral effects not only absolutely inconceivable until he thought of them but also prophesying several modernists. Strauss indeed lavishes care on the musical surface, but it's not the end of him, any more than of Wagner.

Strauss is for me a mystical artist, in the sense that he, like Mahler, seeks to express that which transcends the mundane. Both men use realistic details – cowbells, for example, in Strauss' Alpensinfonie and in Mahler's Symphony #6 – although in slightly different ways. Mahler reaches the transcendent by renouncing the mundane, or at least by raising it. Thus, Mahler's cowbells represent the "last sounds heard by the wanderer on earth." Strauss' cowbells resemble more the birds in Beethoven's Pastorale Symphony: tokens of his delight in the beauties of this world; the intensity of that delight leads him to the transcendent. A Strauss orchestral work is almost never merely realistic. At some point, you will find a major section that has absolutely no realistic impetus at all. Beneath the surface lies a beating heart. The great Strauss conductors find it.

Entries appear chronologically and without subcategory (like tone poem, concerto, etc.), due to my difficulty categorizing much of Strauss' output. Is, for example, Eine Alpensinfonie a symphony or a tone poem? Is Don Quixote a tone poem or a concerto? I have tried to limit myself to performances currently in print, although I've violated that rule a couple of times to include interpretations which devoted Straussians should watch for. Finally, the year at the end of each entry refers to the recording date, unless otherwise noted.

- Also sprach Zarathustra, Op. 30

- Aus Italien, Op. 16

- Burleske in D minor

- Der Burger als Edelmann - Suite, Op. 60 (Le Bourgeois Gentilhomme)

- Don Juan, Op. 20

- Don Quixote, Op. 35

- Ein Heldenleben, Op. 40

- Eine Alpensinfonie, Op. 64

- Festliches Praeludium, Op. 61

- Josephslegende, Op. 63

- Macbeth, Op. 23

- Metamorphosen

- Panathenaenzug, Op. 74

- Parergon zur Sinfonia Domestica, Op. 73

- Schlagobers, Op. 70

- Tanzsuite aus Couperin, Op. 107

- Till Eulenspiegels lustige Streiche, Op. 28

- Tod und Verklärung, Op. 24

- Sonata for Cello and Piano in F Major, Op. 6

- Sonata for Piano in B minor, Op. 5

- Sonata for Violin and Piano in E Flat Major, Op. 18

- Piano Quartet in C minor, Op. 13

- Sonatine #1 in F Major for Wind Instruments "Aus der Werkstatt eines Invaliden"

- Sonatine #2 for Wind Instruments "Frohliche Werkstatt"

- Suite in B Flat Major for 13 Wind Instruments, Op. 4

- Concerto for Horn #1 in E Flat Major, Op. 11

- Concerto for Horn #2 in E Flat Major

- Concerto for Oboe in D Major

- Concerto for Violin in D minor, Op. 8

- Duett-Concertino

- Divertimento nach François Couperin, Op. 86

- Serenade for Wind Instruments, Op. 7

- Symphony in F minor, Op. 12

- Sinfonia Domestica, Op. 53

Copyright © 1994-2008 by Steve Schwartz & Classical Net. All Rights Reserved.